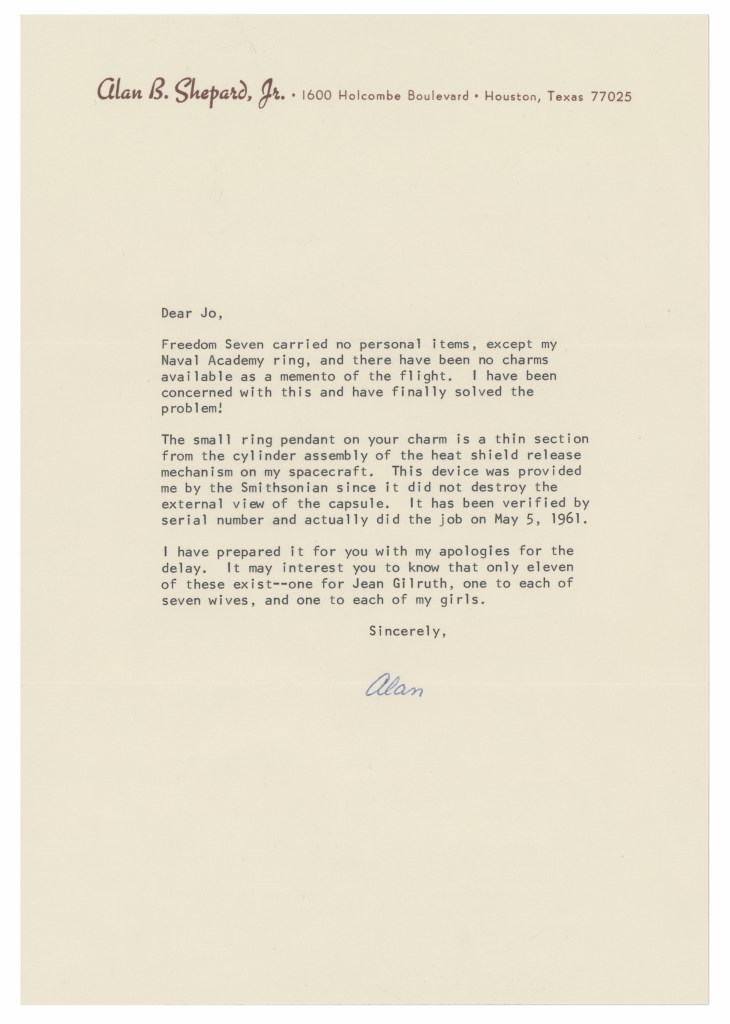

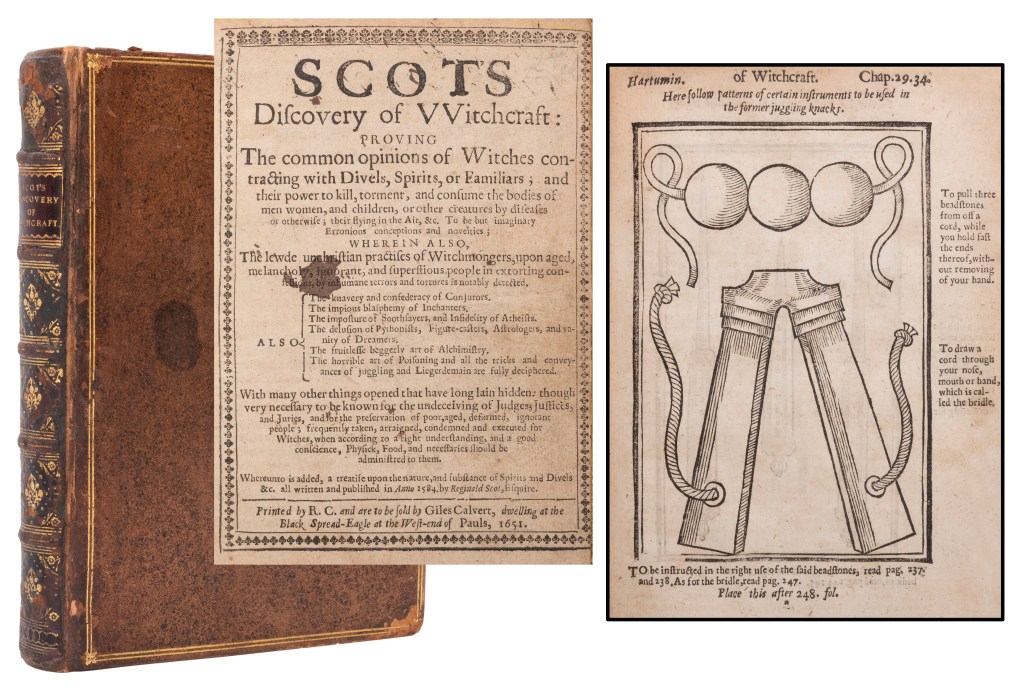

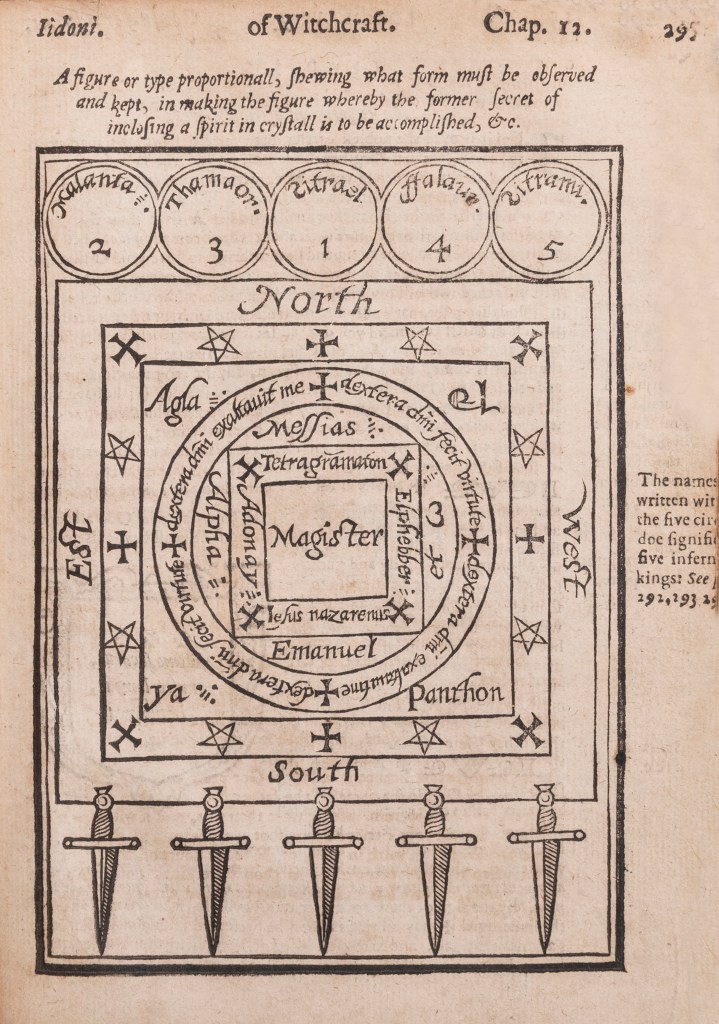

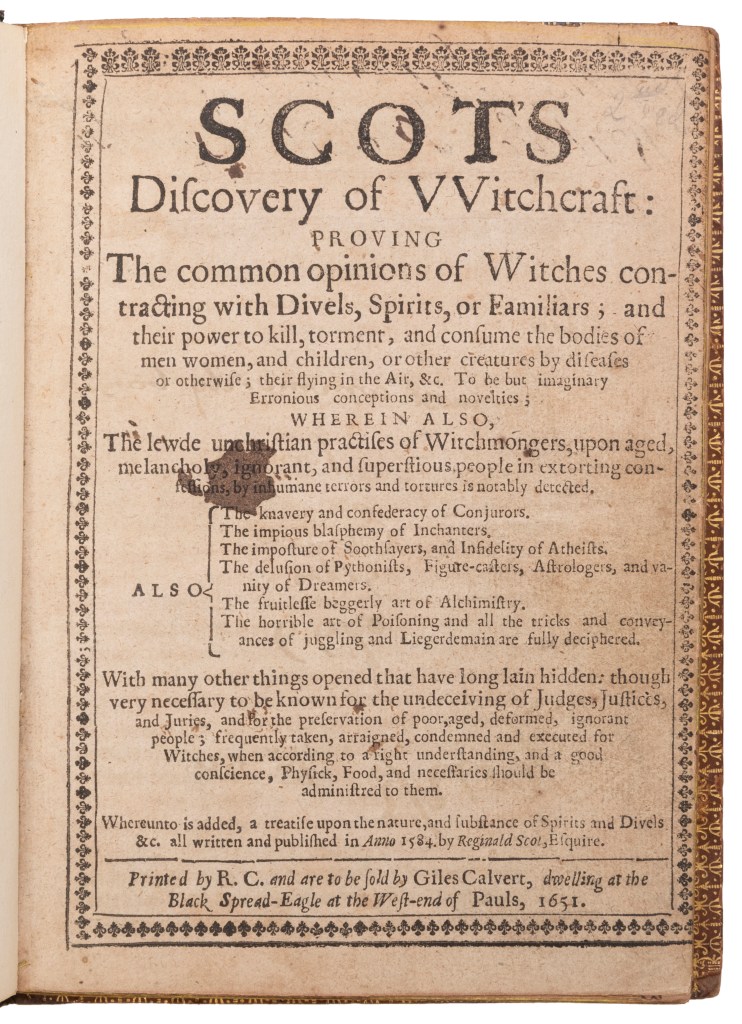

RECORD! A Caille Double Slot Machine Commanded $420,000 at Morphy Auctions in 2017

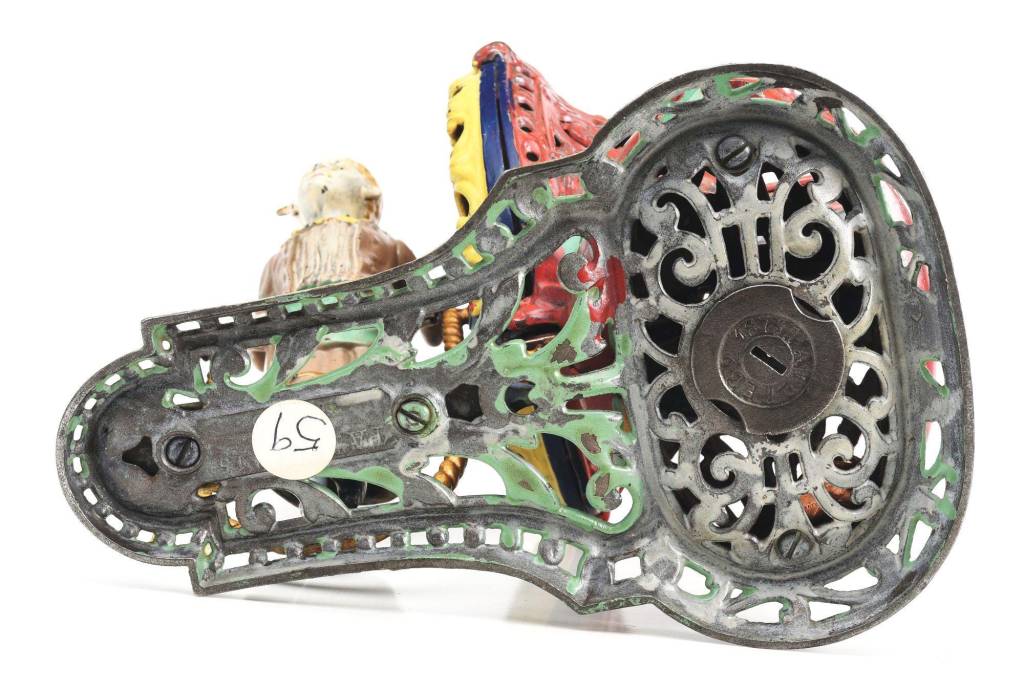

What you see: A nickel and quarter “slant front” double Venus musical slot machine, made with an oak case circa 1905 by Caille Bros. Estimated at $400,000 to $600,000, it sold for $420,000 at Morphy Auctions Las Vegas and set several auction records, including records for any antique double slot machine and a record for any machine by Caille.

The expert: Dan Morphy, president and founder of Morphy Auctions.

First, let’s talk about the Caille Bros company, and what its reputation was when it made this Caille double slot machine. They began in the late 1800s, and were known for producing very well-made, dependable machines. They were all hand-built. Caille had the reputation for building the best at the time. [The company appears to have gone out of business in 1937.]

Why are Caille gambling machines still collected today? They stand out now because they were known for making machines that had great eye appeal and great mechanics. They spent a lot of time perfecting their machines, so they’re more scarce than [those of] other makers.

And how is “Caille” pronounced? It seems like there’s no one way to say it... I’ve heard everything–kale, cowlee, kaylee. Most coin-op guys say “kaylee.”

This Caille slot machine is described as a “double”. Could you explain what that means here? There are two slots, two machines in one. [This model accepts nickels in one slot and quarters in the other.] Doubles obviously cost more to make, and were probably made for the most prominent saloons and gambling halls.

I understand this Caille double slot machine is one of three of its type that survive. Do we have any idea how many might have been made? And is this the sort of thing that would have been listed in the Caille catalog and produced only as orders came in? It would have been a special order for the most part. It was top notch, and difficult to make. If I had to guess, they may not have even made a hundred. A lot were destroyed over the years.

Destroyed? They were against the law [in many places]. They [the police] didn’t want to haul them off. They were heavy. They took them to the parking lot and destroyed them. They would burn them–pile them up and light them on fire.

Have you seen the other two Caille double slot machines of this type? How do they compare to this one? They’re all very similar, and all have had a similar level of restoration work. They’re over 110 years old–they’d need refinishing, and the castings and the springs would have to be maintained. I don’t want to belittle the other two, but if I’m not mistaken, this is one of the most original and complete examples known.

And I take it this model is an especially desirable Caille double? It’s considered to be a Holy Grail of upright slot machines. It’s probably the most attractive double ever.

The Caille double slot machine is described as “musical.” What sort of music does it play? You get one play [one song] for a nickel and three for a quarter. It plays classical music. I don’t know the tunes offhand.

So it was kind of like a jukebox? It played music while you gambled? A press of the lever would trigger the music box and make the wheel go round. The music would continue to play even after it was being operated.

Would it play the same music for each slot machine, or did the nickel side play one tune, and the quarter side played different tunes? I believe there was only one music box in the center [of the oak case]. It was a metal cylinder, like a regular tabletop music box, and it was triggered by either one of the machines, the nickel or the quarter.

How would the music mechanism know whether the player had inserted a nickel or a quarter? It depended on the side you played. The right gave you three plays, and the left gave you one. You pushed down a lever [on the corresponding side] to make it work.

How would this Caille double slot machine have been used? It was made for public consumption. They went to higher end saloons and most likely, country clubs. They were expensive back in the day, compared to regular, run of the mill machines.

What can we tell, just by looking, how difficult this Caille double slot machine was to make? The mechanics of the machine were standard, but the oak case, the tin lithographic wheels, the iron castings were better than anything else on a regular machine. Especially the iron castings–they were much more elaborate, and much more work went into them. From the coin receiver to the handles, it was fancier.

What’s your favorite detail on this Caille double slot machine? The overall look of the front of it. It has a slant front to it, which is unique. I don’t know of any other machine produced like that. The tin wheels are beautiful. The styling of the iron castings are special. There’s a great look to them, great eye appeal.

Was Caille the only manufacturer that got this elaborate with the iron castings for its gambling machines? They didn’t put them on other machines. This particular model had all the bells and whistles. And it’s also a very well-made machine. These were workhorses, made to last.

Yes. This is a good place in the conversation to point out that, then as now, angry losers would take their frustrations out on these slot machines… [Laughs] You’ve got a bunch of drunks hitting it, punching it, and it’s getting a lot of use. Gambling is gambling.

Do we have any clues as to why this particular Caille double slot machine survived in such good condition? If I’m not mistaken, it was only in two families, and it wasn’t moved around a lot. It was always revered as something special. Therefore, it lasted.

Do we have any idea where the Caille double slot machine was first installed? That I don’t know.

But it wouldn’t have gone to a robber baron’s mansion, yes? It would have been commissioned for a public venue? When it was first produced, yes. But I believe it descended through the families. Whoever owned it originally [might have run a] saloon or a hall.

The Caille double slot machine was sold in working condition. How important is that? If it didn’t work, would it be worthless? It’s all reparable. Guys have been doing restorations and repairs on these from the day they were made. It’s almost a lost art. A dozen guys could take apart and rebuild this entire machine, but not a lot of younger guys could fill their shoes. The number of guys who know these machines will decrease with time, unfortunately.

What is the Caille double slot machine like in person? It’s a beautiful piece. It has great detail, great color, great eye appeal, great presence. Even when it was in the consignor’s house, among the rest of his collection, it stood out.

Did you play the Caille double slot machine? Yes.

What was that like? It was fun! [laughs] A nice, smooth-running machine.

And the 2017 sale at Morphy’s was the first time one of the three known musical Caille doubles went to auction? It was the first public auction, to my knowledge.

How did you set the $400,000 to $600,000 estimate? It is hard to establish estimates for pieces that are unique. But I looked at what standard doubles sell for. They go for a range of $80,000 to $120,000. This machine is 50 times more rare than those others.

What do you recall of the auction? It sold in Las Vegas. We had a good crowd that day, 120 to 170 people there. There were three to four people bidding up to the $150,000 range. At the end, it was two guys, going head to head.

The Caille double slot machine notched a world auction record for its make and model because it was the first to sell at auction. What other records did it set? Is it a record for any Caille machine? Yes. And I don’t know of any [other] doubles that have brought over $200,000.

How long do you think the record will stand? I don’t know. Hopefully, we’ll break it next year [laughs].

What’s out there that could break the record? The same machine, or one of the other two. Now if a true triple [an antique gambling machine that features three conjoined slots rather than two] came up, it would probably bring more money. An original triple should bring $400,000 to $500,000. I don’t believe a triple has ever been to auction.

Why will this Caille double slot machine stick in your memory? Because of its eye appeal, its originality, and because I know how rare it is. I’m in a great position–I get to see lots of private collections. It [this machine] is just not out there.

How to subscribe to The Hot Bid: Click the trio of dots at the upper right of this page. You can also follow The Hot Bid on Instagram and follow the author on Twitter.

Ahead of the October 2017 sale in Las Vegas, Morphy Auctions produced a short video about the Caille double slot machine. It features several closeups on its choicer details and shows the machine dispensing coins, but does not include audio of the machine playing music.

Images are courtesy of Morphy Auctions.

Please share this story on social media! It helps The Hot Bid grow.