SOLD! The Talking Skull Automation Fetched (Scroll Down to See)

Update: The Willmann talking skull automaton sold for $13,200.

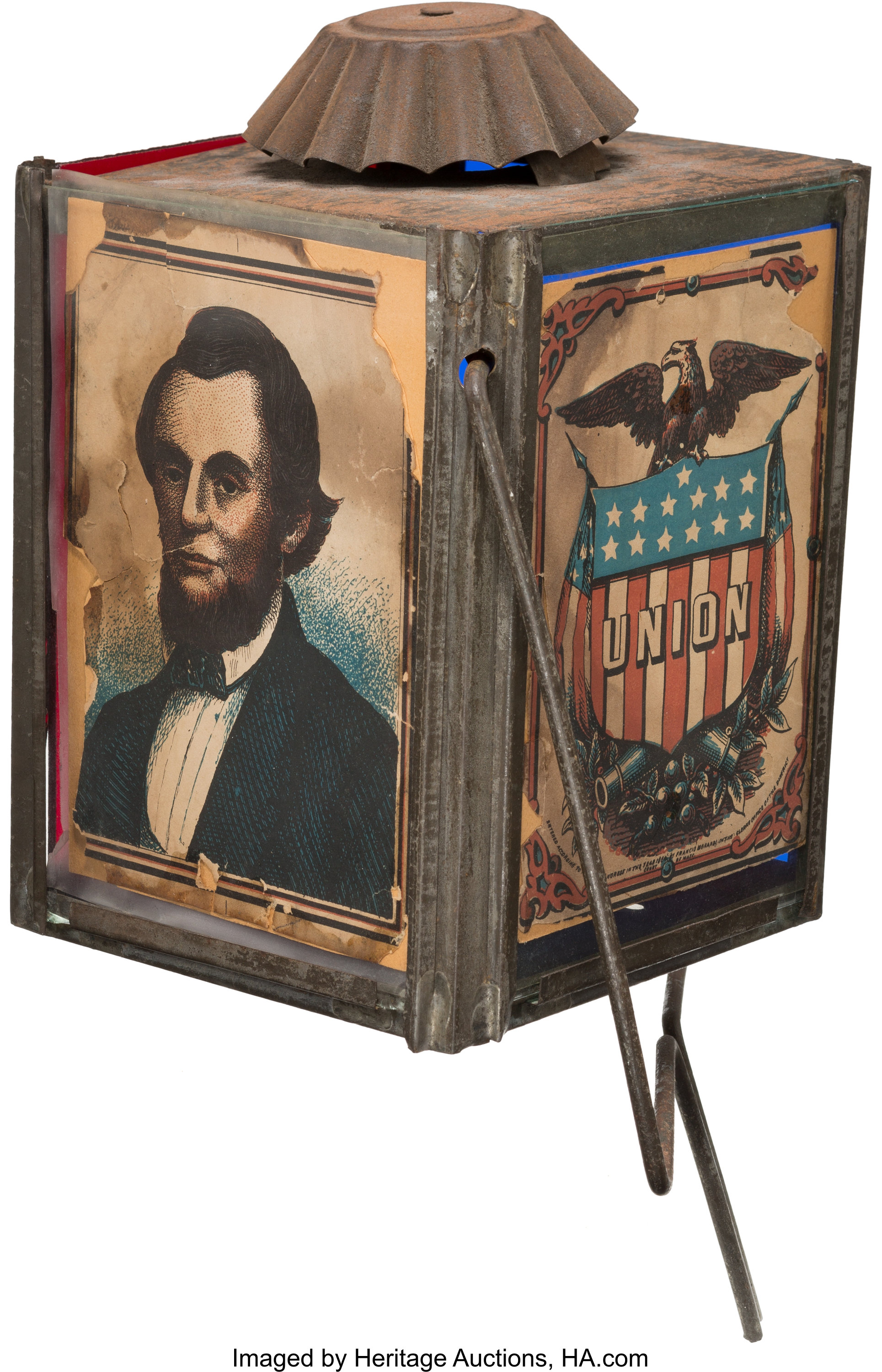

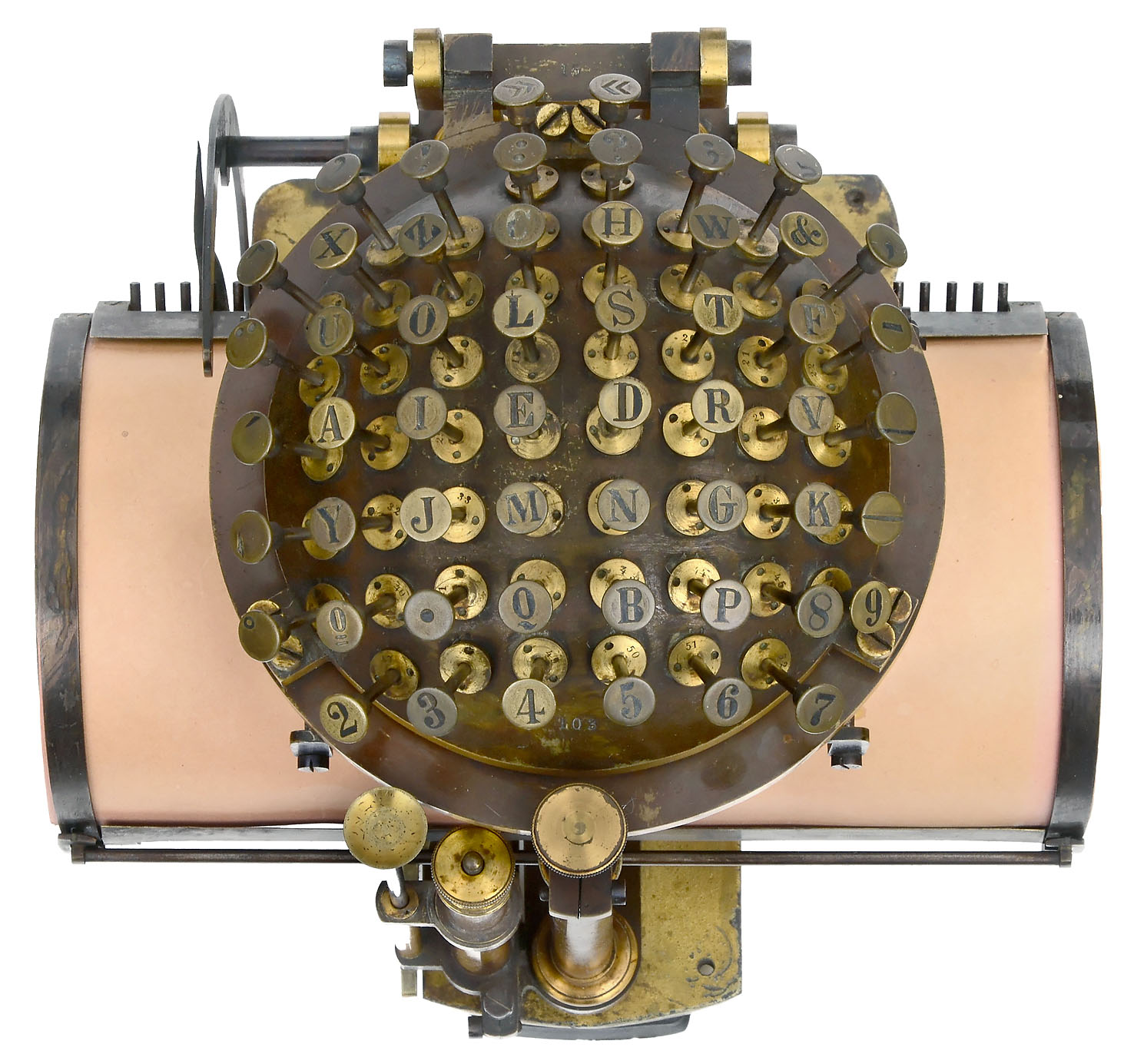

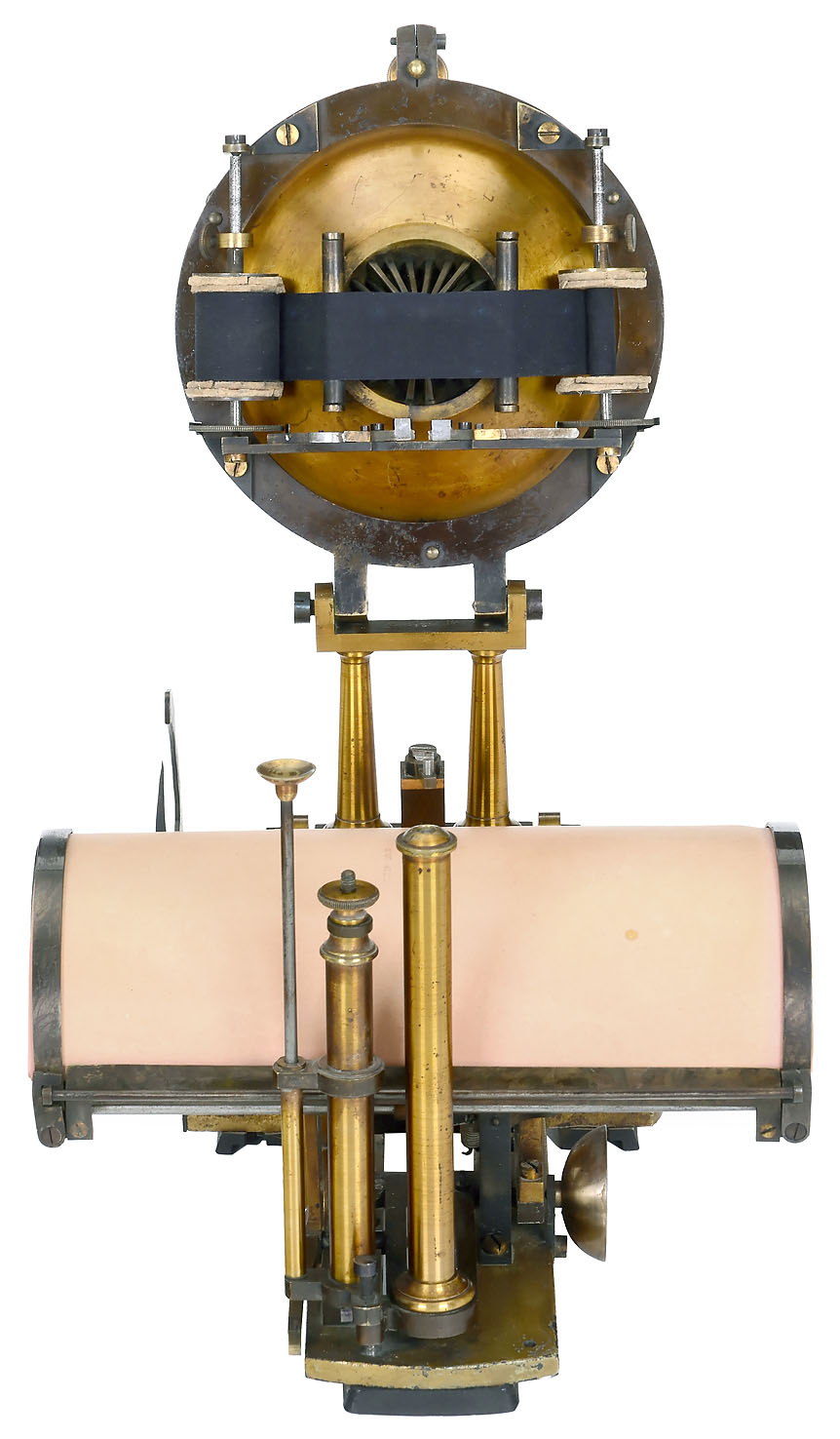

What you see: A Willmann talking skull automaton, made circa 1930 in Germany by designer John Willmann. Potter & Potter Auctions estimates it at $6,000 to $9,000.

The expert: Gabe Fajuri, president of Potter & Potter.

So, how far back does the talking skull routine go in magic? How old is it? It’s over 100 years old. There are catalogs from the 1870s showing talking skulls in them. There are many different ways the trick can be accomplished. This is one very elaborate method.

How do magicians tend to use a talking skull in their acts? It’s actually a conversation between the performer and the audience, carried on with a disembodied skull. The skull is introduced with whatever patter the magician chooses to use. Then the skull is put on display and the magician or the audience asks the skull a question–“What card did I choose?” Its jaw will click the answer out as if it were alive.

Was John Willmann known for creating top-of-the-line automata around 1930, when he made this talking skull automaton? Yes. John Willmann was probably the.. I’m not sure if “famous” is the right word, but he was the most prolific builder of illusions and stage effects of this period [in Europe]. He was kind of known as the master craftsman from pocket tricks to automata and everything in between.

The lot notes describe the Willmann talking skull automaton as “perhaps the most elaborate talking skull ever constructed.” What makes it so? The fact that it uses a real human skull, and the way it artfully conceals [its clockwork] in the faux book. Without revealing too much, most have a very simple mechanism to animate the skull. This is so elaborate as to almost be ridiculous. We’ve sold many examples of the talking skull. We’ve never sold one as complicated or as fanciful as this. This is truly an automaton.

But isn’t it risky for a magician to depend on an elaborate device to make a trick work? I would agree with that. You better make sure you wound it up.

What advantage does the Willmann talking skull automaton give to a magician that a simpler version of the trick does not? It requires no secret assistants to operate, which many other methods do. And a magician does not need to touch it or be near it. He could sit in the front row and carry on a conversation. The McElroy talking skull sells very well and has literally no mechanism. It’s literally a skull made out of composite material. The Willmann thing is the antithesis of that. It’s a robot.

The lot notes describe the book as “a true masterpiece of Willmann’s mechanical abilities.” What makes it a masterpiece? It combines the aesthetics and mechanics into a shining example of what he was capable of. He literally had a small factory in Germany to make these things. It’s a combination of art and science. And you know it’s a real human skull.

Do we know where Willmann would have gotten a genuine human skull? A medical school.

When I saw it was German and circa 1930s I freaked out a little and checked to make sure the timing didn’t overlap with the concentration camps. His career was over and done with by the time the war began. I believe the factory was bombed out. And the talking skull could date earlier than the date in the catalog. It’s hard to say.

How did the clockwork inside the book make the skull’s jaw tap? It activated a mechanism that popped out of the book clandestinely, and that’s what moves the jaw.

Is all the clockwork I see in the photographs actually needed to make the jaw tap, or is some of it for show? No. Nobody was supposed to ever see this. Nobody was supposed to know it’s in there. The book is supposed to look like a book. I’m not a mechanic. I don’t know that every last piece is required. But there’s no reason to put in anything that’s extraneous.

Does the clockwork make any noise? It’s pretty quiet. And you [the magician] are going to be talking, and the audience is going to be interacting. There are others [other clockwork-driven devices] in the catalog–an old joke is you need to play a Sousa march to cover it up.

So the magician’s patter and the ambient audience noise is enough to cloak the sounds the clockwork makes? If it’s even that loud. Magicians use silent clockwork mechanisms.

I understand that the fake book contains several leaves, aka pages. Willmann didn’t have to bother with that, but he did. How does the time and effort he lavished on making the book pages show the high craftsmanship that he achieved? It gives you another layer of deception. If you try to “prove” it’s a real book, you can show the hand-lettered leaves. You can “prove,” if you so desire, it’s an ancient book of spells by leafing through it. The cheaper way [of making a talking skull illusion] is a fake book that you can’t open up. He went the extra mile.

Was this Willmann talking skull automaton a one-off, or did he offer it in a catalog? I’m sure he made them one at a time when he received orders. I’ve seen two. That doesn’t mean that others don’t exist.

Is the Willmann talking skull automaton shown in one of his catalogs? I’ve looked through John Willmann catalogs, but I wasn’t looking specifically for this item. It wouldn’t surprise me [if it was in there]. Paperwork that comes with it–it’s all in German–some of it describes the effect, and some of it references a slightly lower-grade version at a lower price.

How many other talking skull devices have you seen that include a genuine human skull? One.

Is that one a Willmann talking skull automaton? No, but I have it here. It was in the same collection. It’s quite different in the way it works, its composition and its method. We’ll offer it next year in the second part of the sale.

Is the automaton fully functional? Yeah. Did I have a conversation in German with it? No, but it is fully functional.

When it’s fully wound up, how long does it operate? I did not time it.

What is the Willmann talking skull automaton like in person? It’s creepy. It’s a real human skull, that talks to you.

Why will this Willmann talking skull automaton stick in your memory? It’s rarity, its aesthetics, its ingenuity. We’ve handled a lot of weird things. This ranks right up there.

How to bid: The Willmann talking skull automaton is lot 281 in The Magic Collection of Rüdiger Deutsch: Part I, taking place at Potter & Potter on October 26, 2019.

How to subscribe to The Hot Bid: Click the trio of dots at the upper right of this page. You can also follow The Hot Bid on Instagram and follow the author on Twitter.

Follow Potter & Potter on Instagram and Twitter.

Image is courtesy of Potter & Potter.

Gabe Fajuri has appeared on The Hot Bid many times. He’s talked about a magician automaton that appeared in the 1972 film Sleuth, a rare book from the creator of the Pepper’s Ghost illusion, a Will & Finck brass sleeve holdout–a device for cheating at cards–which sold for $9,000, a Snap Wyatt sideshow banner advertising a headless girl, a record-setting stage-worn magician’s tuxedo; a genuine 19th century gambler’s case that later sold for $6,765; a scarce 19th century poster of a tattooed man that fetched $8,610; a 1908 poster for the magician Chung Ling Soo that sold for $9,225; a Golden Girls letterman jacket that belonged to actress Rue McClanahan; and a 1912 Houdini poster that set the world record for any magic poster at auction.

Would you like to hire Sheila Gibson Stoodley for writing or editing work? Click the word “Menu” at the upper right for contact details.